(click on image for larger version)

A psychoanalyst looks at Surrealism

A talk by Rick Curnow at the exhibition of Australian Surrealism Adelaide Art Gallery, July October 2003.

I was surprised and, ultimately, delighted to be asked to make comments on this exhibition of Australian surrealist art. It was a surprise because I am a relative ignoramus about the fine arts but I was reassured that my function is to act as a non-expert observer and commentator. And a delight because the exercise has brought me into contact with these wonderful works.

My task today then is to think about what relationship, if any, there is between surrealism and psychoanalysis. With this in mind, I first went to accessible literature psychoanalytic journals going back over some 20 years or more expecting to find a rich seam of ideas to plunder. I was astonished that there are remarkably few articles on the visual arts in my specialist journals, and that they are almost completely bereft of references to the artists or images of surrealism. (Endless references to literature, and the cinema but visual arts draw a near blank.) It¹s interesting that the surrealist artists have so enthusiastically embraced the ideas of psychoanalysis, but psychoanalysts have not returned the compliment. I guess this may be, in part, because analysts deal in words, basically psychoanalysis is a talking treatment and are less comfortable with the ambiguities of the visual image.

Incidental reading turned up some interesting facts. I learned that Freud was utterly puzzled by the surrealists. Andre Breton asked him to comment on their work, and Freud replied that he did not understand "what the surrealists wanted." (Interesting that he said the same about Woman.) I think it likely that the Lacanian school of analysis would have more immediate understanding of the aims and vision of the surrealists. However, I also learned that Dali visited Freud in London shortly before he died, and Freud was fascinated by Dali¹s work and ideas, and expressed regret at having missed the opportunity to analyse him.

I take it that most surrealist artists

have seriously studied Sigmund Freud¹s work, so I thought it might be

helpful if I outline Freud¹s views of the unconscious, to enable us to

think about their work in that context. Freud said that we each have an

unconscious that is maintained by a rigorous censoring system that does

not allow us access to our unconscious thoughts. Repressed ideas can

only become conscious when the censor relaxes, eg in dreams, or

arguably, in the creative process. The unconscious, in Freud¹s view, is

governed by a process of thinking that disregards logical connections,

permits opposing ideas to coexist simultaneously, recognises no

negatives, has no conception of time, and represents wishes as having

already been fulfilled. It is also a process that makes use of

short-cuts such as condensation, which allows one single image to stand

for several unconscious ideas. I can believe that an artist such as

James Gleeson would be thoroughly conversant with these ideas, and that

they inform the nature of his work.

I want to put forward a proposition that, in looking seriously at these paintings, we are as an audience placing ourselves in a relationship to the art works which is analogous to that of the analyst to his patient. To develop this idea, I must explain briefly what I consider to be the essence of my work as a psychoanalyst. My aim is to get in touch with the patient¹s emotional world, and to do so I listen. I listen for hour after hour over months and years with the aim, fundamentally, of gaining a profoundly intimate knowledge of a particular patient¹s mind. This is an exploration of their inner world, to learn why they have become emotionally unwell to an extent that necessitates such an arduous undertaking. As I listen I will make use of my own mind and all the experiences and emotions of my own inner world to interact with the other person¹s world. Some analysts use the word "reverie" to describe this process of listening and acceptance of whatever emerges from the other person. Hopefully, out of this process of reverie a sort of transformation may take place which will allow for deeper understanding of the other¹s experiences. (Of course, if things go well between a mother and her infant, I am also describing exactly what happens in a child¹s development. I mention this because I¹ll refer back to this idea.)

A surrealist artist has short-circuited this process. The artist has the deliberate intention of revealing something to us that is intensely personal about their inner worlds. They bring these works of art to us with a hope, I assume, that we will stand in front of them and indulge in exactly the same act of reverie that exists in the analyst with the patient.

The artists want to let us know as much as they are able to know of their internal emotional response to their chosen theme, as it has been revealed to them in their dreams, their introspection, and emotional responses. I take it that this is in fact the working definition of surrealism:- that the artist has attempted to heighten the external worldly reality of a theme or image by adding to them the reality of images drawn from his internal world. They invite us to join them in contemplating the imagery of their internal world This is why these particular works make such a powerful emotional impression on us. Perhaps this also explains why the imagery has an air of vague familiarity (to me, at least). I could speculate that there is some sort of shared language of the unconscious which may cause a shock or stirring of recognition when we see these images. After all we all share the same beginnings the experience of mothers and breasts and milk and evacuations and all that paraphernalia. These are images we all share in our emotional world, and we may recognise them intuitively. Someone said to me of McClintock¹s "Approximate Portrait in a Drawing Room" : "That¹s a bleeding vagina under his head." And it was at once recognisable to me as such and it was immediately familiar and shocking. We probably all know such imagery in our dreams, whether we remember it or not.

(click on image for larger version)

Even when we are confronted with the

strangeness of the different universes created by James Gleeson, there

is still a familiarity to the imagery. We recognise those intestinal

folds that become biting fangs that pose a threat of dire engulfment

(in his "Funeral Procession in a Wounded Landscape"), and

that drama that seems to be poised between a sexual act and something

that will devour the actor (in "Pretext of Accident").These

things are strange and yet familiar to us. I find it helpful that

Gleeson does offer me an aid by placing the human figure, often a male

nude, as a locus for my immediate attention and then the metaphor of

a journey, or of linking images to guide my eye through his vividly

imagined landscapes. Incidentally, I never think for a moment that this

is the work of a madman, a psychotic. This is the work of a man very

accepting of his own internal world.

As a psychoanalyst, I don¹t pretend to any greater expertise than the next person in offering an interpretation of any individual work in fact, I think it¹s impertinent to offer interpretation in that way. One would need to know enormous biographical detail of the artist¹s life to even begin to offer individual interpretation. (The famous surrealist, Magritte, and this exhibition¹s Clifford Bayliss both scorn psychoanalytic interpretation of their works.) Any such interpretive comment would of necessity be reductive. As one says of music: if I could say it in words, I wouldn¹t need to write a symphony. Thus, my comments reflect my own responses, and are not meant as definitive many of you will have far more imaginative and detailed responses than I offer.

I refer throughout this talk to an "internal world". I actually prefer this expression, rather than talking about "the unconscious" which always sounds like an organ or thing that exists in my right temporal lobe somewhere. I make an assumption that we each contain within us a unique emotional world of feelings, images, representations of important people and the relationships we have conducted with them. This rich internal landscape grows and develops within us from birth onwards. It influences all of our emotional life, and governs the way we relate to and experience the world outside us. Analysts share with surrealists a great respect for this internal world.

Which is a way of introducing my discussion of Clifford Bayliss¹ "Man Wearing a Bowler Hat", which seems to me fearsome, remarkably sinister, and ferociously humorous. In a face reduced to stylised sweeps and curves, the mouth is a metallic grille, and the eyesockets are replaced by a bleak desolate landscape. It is as though we can look into this man¹s eyes and see the empty lifeless vista that is his internal world, and that reflects back to us the awful emptiness of the external world he has known. Campaign ribbons and a red poppy indicate this man has seen active service, and we note that the painting is dated 1945. It seems that this may be a comment on the horrors seen in a world at war. For me, the melancholic humorous note is struck by the bowler hat, which is a deliberate borrowing from the Belgian surrealist, Magritte, who used it in his own art as a "fright stopper". For Magritte, the hat was a stopper, a plug, that sat on his head to hold in (as a plug stops the water) the frightened feelings that troubled him. Surely the hat serves a similar function for Bayliss enabling him to provide us with a deadpan humdrum image that contains an appalled recognition of terrible realities.

The same bowler-hatted figure appears in another ambiguous and frightening drawing by Bayliss: "Nude with Hair Caught in a Door." Is he a participant in a sexual scene here, or is he an observer? (A classic way of describing the role of the analyst in relating to the patient is as "participant-observer" both participating in an ongoing emotional relationship, and yet at the same time standing back as an observer. The artist seems to me to have cleverly caught something of this ambiguity.) And the female figure: is she submitting passively, or is she struggling in fear? The work is taken into the surreal, away from mere titillation, by the weird intrusion of an animal (cat? dog?) through a vulval-like slit in the wall. The spectator is left feeling uneasy are we being invited to join complicitly in an enactment of a sleazy fantasy, or are we merely to observe do we struggle, or do we submit to the skill of the artist¹s portrayal of the scene? Again, noting the date as 1945, there is also a possibility of considering the image as an allegory of war.

I¹ll talk some more about the effect of trauma on personality and the reparative use of art. Psychic trauma is a term used as a metaphor to describe the sense in which the mind itself can be pierced and wounded by events. Freud suggested that the mind is, in health, surrounded by a protective skin, or protective shield. When all goes well, in a child¹s development, as I suggested above, the protective function is provided first by the mother. As we age, we take on this protective function ourselves, as an aspect of our own personality. Traumatic events of whatever variety (loss of loved ones, sexual assault, bushfire, accident, war experiences) leave one feeling overwhelmed and, importantly, alone. It is as though the protective presence has deserted the victim, who is left alone and defenseless. The sense of devastation extends into the very core of the victim¹s sense of identity. (Examples abound eg. the survivors of child abuse who seek help) Psychoanalysis suggests that it may be helpful to be able to allow the trauma to be thought about consciously, to be re-experienced in the presence of another who can be empathic in the role of witness.

Some of the works we see here can be examined from this perspective. At the core of the traumatic experience is a sense of loss, particularly of loss of the beloved protector who one needs desperately to be present and available. Representation of the experience in art may set up a resonance which responds to that loss. Look at Klaus Friedeberger¹s "Camp Dream". (Friedeberger was interned in Australia in the 1940s.) A camp inmate, utterly alone in the night howls on his camp stretcher, with his mouth echoing Munch¹s "Scream". He is enclosed in a claustrophobic space, whose exit is patrolled by dangerous looking beasts. A sketchy structure in the background seems to offer no hope of escape. And in an alcove/doorway on the right we can see a figure of uncertain gender that lurks, looking on.

To my mind, this painting encapsulates what makes these works so powerful. To state the obvious a realistic portrayal of the internee¹s imprisoning camp would not have the same power. It would provide nothing more than evidence of reality think of the disturbing quality of a TV documentary on the detainee camps. Disturbing but ephemeral. What Friedeberger gives us, in addition to his documentary reality, is the reality of his internal experience. He can draw upon his own internal world to bring forth Munch¹s scream, the beasts, the enclosing space, the darkness pressing in upon him. And the watcher. Once again we are left unsure whether this indeterminant figure is actually an observer or a participant in the protagonist¹s distress.

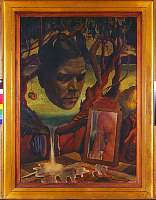

Hein Heckroth¹s "Australia" makes a similar effect. He was also a detainee in 1941. In this case a rather bizarre, vaudeville quality is counterpointed with figures in the lower part of the frame, of a rather threatening dog-like creature, advancing on a dejected, realistically portrayed man (evidently a self-portrait) crawling across a space for which the self-involved stars have no current use. Again, he is a fellow we can reach in an act of empathic understanding. Our current refugees, detained in camps would surely respond with immediate recognition to this drama. Perhaps an artist amongst them will be able to articulate equally powerful images to trouble our consciences.

And what did Joy Hester fear when she created "Fun Fair"?

I find this the most frightening image

in the exhibition, especially as it has been cropped and framed in

Bruce James¹s book. Was this a comment on her situation as a woman in a

predominantly male creative world? The biographical notes let us know

of her troubled emotional life, but one needs more specific knowledge

to answer these questions. Nonetheless one must respect the power of

her violently juxtaposed images which pose such threat to the female,

all in the name of Fun at the Fair.

Because I¹m a psychoanalyst, and a therapist, I am drawn to the paintings that seem to express an evident degree of anxiety or trauma. And it seems that surrealism is a wonderful vehicle for such expression. But it also has a more genial aspect. This put me in mind of another bit of psychoanalytic theory which I think some of the works epitomise.

A British analyst called Winnicott was one of the first of us to become intensely interested in studying the importance that the presence and nature of the mother-child relationship had on the developing infant¹s mind. One of his more charming ideas was that if things go well in this mother-infant relationship then the infant develops what he calls "a capacity to be alone". (As though the infant can feel "I am safe with this mother person and so it is OK for me to drift off for a time into my own world because she is a safe mother it is not necessary for me to cling with anxious terror to her for fear that she will forget and go off and leave me forever. I am safe to be alone")

Winnicott was interested in the origin of the creative process in early childhood experience, and he thought that this capacity to be alone could be its earliest precursor. He described a quality of "unintegration" in the infant who is able to be alone in this way meaning I think an ability to let go of the pieces of one¹s personality and simply drift and be available for whatever experience may come along. We may experience something like this as adults when we drift into a comfortable sleep and experience random chaotic thoughts without anxiety.

These ideas came to mind immediately when I saw Sidney Nolan¹s"Girl with a Curly Line". I am sure that, as a painting, it is exquisitely crafted, but the impression it creates is of delightful carefree thoughtlessness. It is a clear example of what the surrealists call "automatism". I had trouble with this concept. I understand that it means allowing a free flow of expression, unsullied by the censoring processes of rational thought. But this doesn¹t sit so easily with images as beautifully crafted as these we see in this exhibition. These are images that have been worked up very thoughtfully. However, in listening to James Gleeson on his video, one learns that he does seek to be open to whatever image might emerge from his internal world of thoughts and feelings, which he then attempts to capture and work upon. If that is what is meant by Automatism, then it might very well equate with the state that Winnicott terms Unintegration. I mean that Gleeson may have a great facility for being open to the fleeting images that emerge from his inner world just as some people have a remarkable facility for remembering dreams.

I¹ll return to the darker side briefly.

Winnicott contrasted the state of Unintegration with an altogether

different experience which he called Disintegration. The child is left

in this state when the protective mother¹s presence is not there. Then

we fall apart in a terrifying way. This is what fear of breakdown is

about in our adult life. Geoffrey Graham¹s "Dreams Beyond Avarice" seems to capture something of this quality. The dreamer

summons an erotic image, but is threatened and almost overwhelmed by

the tossing ghostly forms that invade the canvas as though the erotic

wish itself could summon up all the forces of disorder and madness,

leaving him alone and isolated in his bed, beset by nameless terrors.

In preparing this talk I have learned with great pleasure how easily the two disciplines, psychoanalysis and surrealism, share some central ideas. I might boil this down by saying that both recommend an honest appraisal of one¹s inner world, no matter how painful or messy that may prove to be. It is salutory to look, as unflinchingly and honestly as we are able to bear, at the quirks and foibles and memories and fantasies that make up our internal world. Then we may come to a deeper awareness of our own reality, and more acceptance of the reality of another¹s experience.

I¹ll conclude by taking over a quote from Bruce James¹ book (I¹m not sure if it should be attributed to Bruce James or James Gleeson) and substituting the word "psychoanalyst" where he has written "surrealist". I hope whichever author will forgive the somewhat surreal juxtaposition of my own world into his. My amended quote reads as follows:

"Everyone remembers the strangeness of psychoanalysis, its disturbing vistas and dissociated narratives. Everyone remembers the cruelty, which it does possess, and the fearfulness, which it can provoke remembers the bite. But within that, it¹s easy to forget a crucial fact about psychoanalysis. It was not simply a movement meant to unleash the forces of the subconscious, liberating analyst and patient alike from mundane habits and constraints. It was also meant, as a practical result of this untethering, to make people happy. Or happier. Above all, psychoanalysis was a gambit for emotional betterment through the pleasures and mysteries of the image/knowledge of the internal world."